Image: @jasonramasami

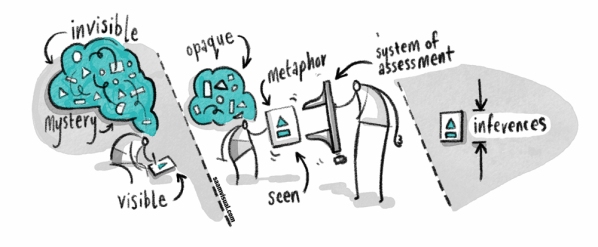

I have read David Didau’s two recent posts on assessment – here and here – with interest. David is rightly sceptical about the efficacy of assessment rubrics and has summarised the problem succinctly: “We need always to remember that any system of assessment is an attempt to map a mystery with a metaphor.” In other words, as student learning is invisible and opaque and written work is only a proxy for learning, we must be careful about the inferences we draw so that we avoid over-simplified judgements.

This has got me reflecting on how I have assessed students in my English lessons over the last few years. What follows is not advice, just a description of the developments I have been through. About three years into teaching, I stopped using descriptors almost entirely, especially with my key stage 3 classes. I would pay lip service to APP and the like, but in reality I would read the child’s work and award a grade based on gut instinct. Although I kept my little secret to myself, this never became an issue: in standardisation meetings my marking was no more or no less accurate than anybody else’s. It is easy to put work in rank order and assign a grade; it is much harder to explain why. These days, when I want to communicate or learn what quality work looks like, I always seek out examples and models to share or adapt for teaching.

My theory is that the mental models we develop as teachers – of a) what progress and standards look like in our subjects, and b) where individual students are in relation to these – are of far more importance than lists of crude, meaningless assessment sentences. Consider for a moment the sheer complexity involved in assessing a page of student writing. Any fair and accurate assessment must consider a broad range of aspects, including grammar knowledge/application, topic knowledge, understanding of textual conventions, writing habits, level of effort exerted, working conditions (were they rushing to finish or carefully redrafting?), originality (did they only parrot what they had heard in class or did they make it their own?), etc. In other words, work is the product of many factors, only some of which are visible to the teacher.

Secondly, the accuracy of assessment should play second fiddle to what we should be attending to, which, to borrow John Hattie’s metaphor, is helping students to become ‘unstuck’ – i.e. the way that we we respond to work so a student learns more and learns better as a result. Many social and cognitive factors play a part in this and, surely, these decisions are where teacher expertise really lies.

Below is a paragraph written last week by one of my Y8 students. The class were writing from Lady Macbeth’s perspective:

My assessment of this paragraph is far stronger when I leave rubrics and descriptors to one side. Immediately, I can see a few areas she needs to work on, such as:

1. The paragraphing of direct speech.

2. The unfortunate splice comma habit she has adopted (more noticeable in earlier paragraphs).

3. The unsophisticated syntax – e.g. ‘we both were in our night clothes’.

4. The ambition of vocabulary choice.

5. The depth of insight into Lady Macbeth’s thoughts/feelings.

However, I also know this paragraph was rather rushed; she was writing very quickly in timed conditions and this was the last paragraph. It would be unwise, therefore, to draw too many conclusions about her knowledge and skill levels from this paragraph alone. It would also be easy, for instance, to read this piece and infer that she cannot spell ‘successful’ … but perhaps it was just a one-off slip-up? (She added in the extra ‘s’ after I had circled the mistake.) If I tried to map her against an assessment grid, it would only lead to abstract and unhelpful targets based on the faulty assumption that all children become successful writers by following the same path.

Ultimately, lists and grids of nebulous assessment criteria are a smokescreen, unnecessary distractions that infantilize and over-simplify the assessment process. If I could have my way, I would ditch almost all summative assessment and throw everything into improving my expertise in delivering formative assessment. So that we could pool this expertise, subject departments would regularly meet to share and discuss the work of those tough students’ for whom progress and learning seem intractable.

Like student learning, teacher assessment skill is largely invisible. We need to find more opportunities to make this genuinely tangible.

Related post:

726 ways to achieve good exam results (or why the solution should be smaller than the problem)

As usual I am in excited agreement. I love your posts. They always seem to express ideas that I haven’t been able to articulate myself but get right to the heart of what I think good teaching is really about.

In my school we have never had levels – which helps. I especially like your comment about not over analysing one weak piece. I have recently become very rebellious about taking time to unpick what is wrong and could be better when I know darned well the child has just rushed it and given little thought.

“If I could have my way, I would ditch almost all summative assessment and throw everything into improving my expertise in delivering formative assessment.”

Me too – particularly if it’s for accountability rather than education.

I think, however, that formative assessment, in terms of purpose and what is required to carry it out, is completely different to assessment for attainment data. I’ve tried to resist all attempts to bend formative assessment to the will of summative judgements, though I believe much can be gained from doing it the other way round!

On the other hand, even if we could remove the high stakes, accountability culture that is the driving force for summative assessment (I think), a basic need to know ‘how we’re doing’ seems to exist in a lot of us and, in some research I recently carried out on science assessment (in schools in several different countries), the majority of pupils wished to know such things as grades and levels. There are, of course, many areas which are actually amenable to that type of assessment (right and wrong answer domains) but it’s very difficult in complex, multifaceted subjects. I’m not sure what the answer is, but if it is increasingly acknowledged that what we have is very flawed, then that’s a start, at least.

Reblogged this on Délcio Barros da Silva.

This made me thoughtful, Andy. I see your point, but I did just wonder whether “I would read the child’s work and award a grade based on gut instinct” can work for an experienced, confident teacher but is MUCH more difficult when you’re just starting out on your teaching career.

What do you think?

Hi Jill,

Sorry for the late response – I’ve been in Munich for the week.

I see your point regarding new teachers – ‘gut instinct’ is the result of intuition grown through extended practice over time. I appreciate that what might feel natural to me, might not to my less experienced colleagues.

I speak as an English teacher here, but I think we rely too heavily on abstract criteria; far better to create exemplar banks at different levels/thresholds so that new (and experienced) teachers can check work against them.

Of course, I am thinking about the assessment of extended writing here, Some aspects of grammar/literary knowledge can be assessed as smaller, discrete units (however, there is always the question as to whether this ‘counts’ if it cannot be applied accurately in longer pieces too.)

Pingback: ORRsome blogposts May 2015 | high heels and high notes

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.