In 2013, Ofsted published a pretty damning report about the provision available for more-able students at secondary schools in the UK. One statement from the report rings true to me:

Many students become used to performing at a lower level than they were capable of. Parents or carers and teachers accept this too readily.

The report argued that there are three main challenges for schools: to ensure that our most able students do as well academically as those of our main economic competitors; to ensure that students become aware, early on, of the academic opportunities available to them; and to ensure that all schools help students and families overcome cultural barriers to attending higher education.

I think it is fair to say that individual teachers cannot solve all of these problems alone; however, there is probably much we could be doing better. If I am honest, I have long hidden from the fact that I could be challenging some of my students more than I am, and even though I have long prided myself on ‘teaching to the top’, this has rested on a fairly conservative estimate of what the ‘top’ consists of.

Perhaps the first port-of-call for all classroom teachers is to introduce students to university and further education opportunities as early as possible. We must help our students to consider the long-game: their GCSEs are merely stepping-stones on a much longer journey – even if they mark the end point for us. Not all bright young people will have high aspirations and expectations set at home; for them, we teachers are very important. We can start tomorrow by making a simple modification to our language use – it’s not if you attend university, it’s when you attend university.

It is important to consider the moral argument, too. Every successful society must nurture its finest young minds. And this is not just about the future economic prosperity of the nation; this is also about creating a new generation of thinkers, scientists and artists who will keep us safe and enrich the culture of the future. We talk a lot about improving equity in schools, but this should never be at the expense of allowing some to move way beyond their peers if they can. It is also important that these young people, our future, see beyond the functional and competitive purposes of education. Learning has intrinsic value and knowledge is its own reward. It is a fine message to take into the future.

Let’s take a step back from all this idealism. What can we do every day to help our highly capable students to make progress? While extra-curricular opportunities play an important supporting role, my hunch is that the answer lies in the place students spend most of their time in school: in our classrooms. I think that there are three areas worth considering: content, thinking and shaping.

Content – what will they be learning?

Cultural capital. Whatever we choose to teach them in the limited time they have with us must contribute towards their cultural capital. It is no good being intelligent and hard-working if the knowledge and skills you have gained at school do not help you to become socially mobile. At a very minimum, all able students should leave secondary school with the knowledge and skill needed to read a broadsheet newspaper from cover to cover with understanding.

Coherence and cumulativeness. The curriculum must be carefully sequenced so that students learn new concepts in the context of what they have already learned. This is especially important for disadvantaged able students who rely so much on school lessons as they have nothing else to full back on.

Exam specifications as springboards, not straightjackets. Exams are designed to sample knowledge and skill, not dictate what is taught. An over-focus on exam technique leads inevitably to the narrowing of the curriculum. Sadly, this has the most impact on able students as they require far less time on exam preparation. Once again we need to play the long game: what they learn now can be stored away for the future. Bring in A-Level and undergraduate level content, and lace your lessons with stories and ideas from the great wide world. (And let’s be honest: in a norm-referenced exam system, it is those who are taught ‘beyond’ the specifications who will achieve the highest grades.)

Depth and breadth. Our able children need a broad school curriculum, but must also be given the time and opportunity to explore topics in great detail. A balance is preferable.

Knowledge and vocabulary. It is no use being bright if you are not actually learning anything. Being exposed to high level content is not the same as actually learning it. Expect students to reel off facts with great depth and accuracy. Expect them to use advanced subject-specific vocabulary – and make sure you model this for them. The language culture of your classroom goes a huge way.

Wider reading and research. Twenty-five hours a week is not long enough. Give your bright students extra reading and research to do. This should be more specific than ‘just Google it’. It could include books, journals, carefully-chosen web-sites, news reports and documentaries. You could start creating a bank of extension resources to go with each topic. Make sure you place books in your students’ hands – the personal touch goes a long way.

Thinking – what kind of thinking will they do?

Subject-specific thinking. Your able students need questions and tasks that allow them to think deeply and accurately about the content at hand. As such, you should be mindful of generic approaches to ‘thinking hard’ – such as Bloom’s Taxonomy. Resources like subject-specific ‘question templates’ can help you to get students to think deeply about your subject in an appropriate way.

Integrated extension questions. Teachers often leave the more difficult tasks to the end of the lesson – the ‘extension’ questions. This makes logical sense when working with students of very similar ability, but not when working with mixed-ability groups. Resources and worksheets need to allow students to move quickly on to more challenging material, rather than endlessly completing tasks they already know how to do. (I have a strategy whereby all ‘stretch’ questions are coded in red – students can choose to go to these first if they are ready.)

Probe thinking. As Doug Lemov says: “The reward for a correct answer should always be a harder question.”

Risk-taking. Many of our able students are those who are used to getting things right; this has become part of their identity, and their peers expect them to uphold this. They become typecast if you like. Often these students also like to please their teachers. This, however, is what holds them back. They need to take more risks and ask more questions otherwise it is unlikely that they are learning as much as they could be. They can help to drive the process by taking on the responsibility of asking for harder work.

Shaping – do they know how to create excellent products and performances?

Do we know what excellence looks like? It is important to share student work with our colleagues as often as possible. We should work backwards from great examples to help us plan our lessons. We should also look out to other schools to compare and contrast their top standard with ours – sometimes the only reason that we do not stretch our students is that we do not realise that more is possible.

Do our students know what excellence looks like? We should also share excellent exemplars with students as often as possible – and sticking them on the wall is the least helpful way of doing this. Students need to read them, discuss them and deconstruct them. Furthermore, sharing descriptive success criteria is a pretty useless strategy unless this is accompanied by concrete examples of work.

Live-modelling and upscaling. Complex thought-processes need to be explained explicitly. We need to learn how to model A* standard work and thinking, even if it is difficult for us. Sometimes this can be made easier through upscaling: take an average example and given it the full makeover with the class.

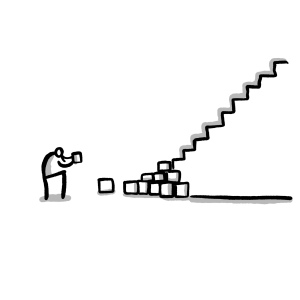

Break down complex procedures. Even an A* student will need guidance on how to proceed with complex tasks. She will also benefit at times from the ‘marginal gains’ approach – this involves sharpening her skill with the constituent parts of a task before tackling the whole.

Parameters versus freedom. Not all bright students are the same. Some need a lot of guidance, support and parameters; others need these to be stripped away. Our knowledge of our students, therefore, should always guide our decisions.

*

My school’s motto is ‘Going beyond our best’. For our weaker students, it is easy to imagine this place beyond current performance. For our brighter students, however, we might need to define it more clearly.

I hope this simple check-list – content, thinking and shaping – can help you to achieve this.

Image:

Image: