Image: @jasonramasami

Your class have been reading a literary work for some time. You feel that it is now time to evaluate a particular aspect of the text – let’s say, how an important character has been drawn. You ask for the class’s ideas – perhaps you first give them a chance to think alone or discuss in pairs. As the ideas come in thick and fast, you create a list or a mind-map on the board. You probe your students’ responses to improve the depth of thought. Soon you have a board covered with ideas. These include defining adjectives, references to pivotal events, vital quotations and links to the text’s social and historical context.

The mind-map is not bad, it’s just that … it would have been far better if you had just told them in the first place.

Recently, I have been thinking about whether literary interpretations should be taught as explicit knowledge – in the same way as theories and concepts are in science lessons. This, of course, throws up a plethora of thorny problems. Aren’t we each entitled to our own opinion? Aren’t all opinions valid as long as we can back them up? Shouldn’t literature encourage free-thinking in our youngsters, rather than straightjacket them with the pedantry of their elders?

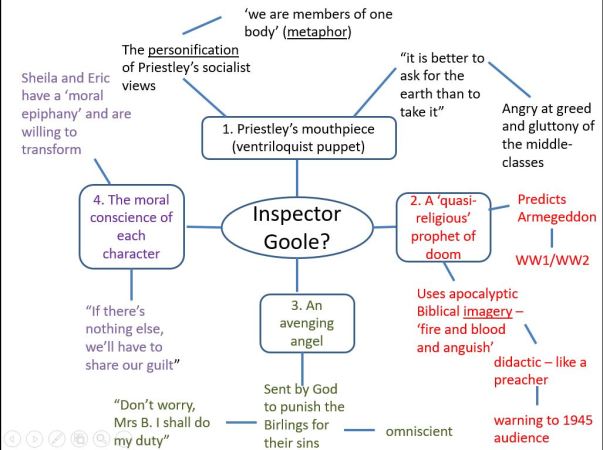

Putting these complications to one side, I decided I would put it to the test. Before my lesson on J.B. Priestley’s Inspector Goole, I picked four of the most interesting interpretations of the play’s enigmatic visitor I could find and created a mind-map.

At the start of the lesson – as normal – I asked my mixed-ability year 10 class for their thoughts on Goole. They touched tangentially on the ideas of moral conscience and the voice of socialism, as well as the predictable he must be a ghost, like ‘ghoul’. Their ideas were interesting and on the right track, but not yet fully-formed.

At this point, I told them that my role was to take their ideas further by introducing them to some of the most interesting interpretations of Goole I had encountered. I revealed the diagram below point-by-point, and we discussed each theory as we went. I gave them time to draw a visual representation of each theory – so as to harness the power of dual-coding. At the end of the lesson, the class divided into pairs and took it in turns to explain each point on the diagram to each other.

By the end of the lesson, every member of this mixed-ability group appeared to understand these theories. I tested them on their knowledge two days later. They had retained the meaning of terms like moral epiphany and quasi-religious.

Perhaps the most interesting moment of the lesson, however, came at the end. A pair had extended upon the idea of Goole as Priestley’s mouthpiece. They had decided that the Inspector should be renamed Priestley’s Parrot. His role is to repeat Priestley’s message of social responsibility and compassion into eternity: on stages, in classrooms, yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Who says didactic teaching cannot lead to creativity and originality?

*

A couple of days later this principle repeated itself. I was working with a year 11 student whose teacher had recently given the class a crash course in Freudian theory. We were looking at an episode from The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde when Hyde savagely murders Sir Danvers Carew and is said to erupt into ‘a great flame of anger’. “Perhaps the ‘flame’ is a metaphor for the way the unconscious mind can suddenly burst through,” she suggested.

In my opinion, if we want to encourage critical and divergent thinking – which we surely do – then we must provide our classes with the tools to do so. If not, then we rely on young people plucking ideas out of the ether, the educational equivalent of alchemy.

Implemented carefully, the explicit teaching of ideas and interpretations need not be restrictive. Instead, it can induct students in the discipline of the subject and spark genuine insight.

Related posts:

Knowledge-first English teaching – a video

The poetry dilemma:to teach or to elicit?

Pingback: Do you suffer from a fear of facts? | Filling the pail

Pingback: 10 prevalent myths about English teaching – part 2 | Reflecting English

Pingback: What happens when we teach interpretations of literature as facts? — Reflecting English | English Literature Reigns !

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Pingback: The Blogosphere in 2016: Roaring Tigers, Hidden Dragons | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: Write the Theme Tune, Sing the Theme Tune | English Remnant World

Pingback: Literature Revision and the Art of Given Spoilers | mrbunkeredu

Pingback: Three Tricks to Improve Explanations | Class Teaching

Pingback: Explicit Vocabulary Teaching 2: What and How? – TomNeedham

Pingback: To see or not to see: that is the question | must do better…

Pingback: On AQA Lit Subject Knowledge Gems | The Learning Profession