Image: @jasonramasami

Having recently been appointed as ‘research and development leader’ at my school, I would like to put down in writing my thoughts about how I see this role working in practice. Much has been written recently about how and whether our education system would benefit from becoming better research-informed, yet there appears to be little joined-up thinking emanating from the multitude of institutes, trusts, charities and school alliances that claim that they want to make this a reality. I shall avoid the dictionary of acronyms this could easily become, concentrating instead on how we want this to look at our school and where we might go from there.

With Shaun Allison, I am working on a three-year project to bring about a research-engaged culture. At present, our approach to research is quite unstructured and ad-hoc. We are already a very good school, yet we believe that creating a more systematic research-rich climate would be an important step for us. We are well-aware that the first stop on our journey to ‘research-informed’ is ‘research-aware’. Thus the two long-term aims I am working towards are as follows:

1. To encourage staff at all levels to become ‘critical consumers’ of educational research so as to create an evidenced-based teaching and learning culture.

2. To develop and support a range of forms of research within the school.

There is no blueprint for how to bring the above about. Indeed, the Education Endowment Foundation have just launched a wide-ranging randomised controlled trial which will focus on the best ways of communicating research evidence to schools and how to encourage schools to engage with it. We will keep an eye on this, but will also plough our own furrow as we seek to work within our school and with local Higher Education providers.

Below are some of the avenues we will be exploring.

Partnership with Higher Education

Next academic year, we will be working with Dr Brian Marsh from The University of Brighton. Our relationship will be reciprocal. Brian will be supporting us by improving our understanding of action research and research methodology. He will work directly with us and our ‘Learning Innovators’ (who will be undertaking year-long action research projects) once or twice a month. The aim is to set in motion a more rigorous action research process. The understanding of sound methodology I hope to develop through this process will be central to its sustainability. On the other hand, we will provide Brian with the resources and data he requires for two research projects. Not only will Brian’s findings be useful in taking our school forward, but we also hope to learn much from working alongside an experienced educational researcher as he goes about his business.

Learning innovators

Our ‘Learning Innovators’ will be required to engage with the wider evidence base as they undertake their initial reading. As a requisite of their projects they will work within their department areas to disseminate their findings as well as present to the full staff body. We hope then that they will be inspired to take evidence-informed thinking into their future practice, promoting a culture of ‘micro-research’ projects within subject areas.

Critical reading culture

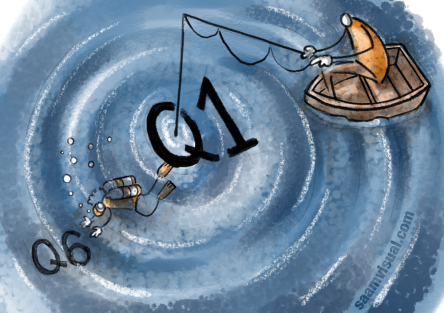

Schools and teachers can easily becoming locked into an inward-looking cycle. To avoid such stagnation, it is vital that our thinking and practice is challenged and influenced from outside evidence too. The cycle is difficult to break, especially considering the pressures of workload and work/life balance. Our first stage will be to help make professional reading part of the fabric of our school. Those of us on Twitter or who read educational books, blogs and research papers regularly can forget a simple fact: many teachers do not read as a professional pursuit. So how do we help teachers become aware of this wider evidence base in light of the truth that much educational research is either very expensive to obtain or written in quite an inaccessible style?

Our first approach will be the EduBook Club. Shaun has written about the practicalities here. In short, all teachers and TAs will choose a book to read, will attend seminars on INSET days to critically evaluate their reading and will consider how this thinking might influence practice going forward. Our DEAR (Drop Everything and Read) time can be used by staff for this reading if need be. The texts range from the Hattie and Yates’ research-based Visible Learning and the Science of how we Learn to Ron Berger’s An Ethic of Excellence. We have wrestled with whether more anecdotal texts like Berger’s should be included but have decided that we want to set in motion a wider culture that looks beyond the school gates for inspiration wherever that might be – such ideas can than form the focus of in-school research and evaluation. It’s also worth remembering that research by its nature plays catch-up: there is much practice across the world that works brilliantly and, as yet, has yet to be given the green light by research. Group members will be encouraged to share new theories and evidence with their peers within subject areas and through our 15-minute forum programme.

Hearts and minds

Alex Quigley has recently written cogently – here – about teacher engagement with research: if it is seen as another stick to beat teachers with the impact is unlikely to go beyond that of lip-service. A research-informed culture must not become dominated by a top-down ‘Ofsted in sheep’s clothing’ approach, nor should it be a free-for-all where dubious findings (learning styles, for instance) share equal weighting with robust findings. I appreciate, however, that the key to the success of our project will be how we win people over. I am already mentally preparing for the launch to staff in September, the message of which will be ‘teaching is an art and a science’. I also know that working the informal structures of the school – staff room chats, for instance – will be vital too as we try to engage and excite more teachers. I love the fact that our subject-based teaching assistants, who have such a wealth of untapped knowledge, will also take part in the reading groups. In line with this, the reading groups will include members of SLT but will not be led by them.

Personal development

I am a teacher and not a researcher. I shall always remain so. Yet I aim through this project to explore the ways my school can inspire ordinary classroom practitioners, like myself, to become engaged with, in and even through, research. I will hold my hands up and admit that I start from a position of relative ignorance. This is important because those seeking to bring about a research-rich culture should not be seen to be working in an impenetrable sphere far from the real world of our colleagues. If we do, we might inadvertently rebuild the ‘ivory tower’ that characterises many teachers’ beliefs about educational research already – only this time under the roof of our very own school! I have a lot of reading to do and there are a lot of collaborative links to be made. We will make mistakes along the way but that is very much in the spirit of what we want to achieve: a school where research evidence can shed light on our successes, our failures and guide us towards improvement.

Questions for the next year and beyond

- How do we ensure that we are in receipt of the most robust worldwide research evidence available?

- How do we communicate these findings in an accessible way without losing any of the finer nuances?

- How do we promote engagement with research to teachers who already have such a heavy workload?

- How do we ensure that we utilise research findings that are sharply focused on the most pressing needs of our students?

- How do we ensure that research evidence enhances what we already do well as opposed to providing a limiting dogma?

- As a ‘research champion’, how to I ensure that my own biases and preferences do not affect the content and breadth of research evidence I promote?

*

The above is just a flavour of our initial thinking. I appreciate that the role of research in education is a contentious issue. Our approach must remain cautious and we must ask critical questions of the research findings we share. However, this kind of scrutiny should not only be reserved for research findings; we should apply it to too to the thousands of hunches and biases that make up much of our day-to-day decision making in schools. Much of this is built on solid foundations of wisdom and experience, but not all of it. If our research-rich climate leads to more questions of ‘why?’ or ‘might it be better like this?’ then its effect will surely be positive.

In this previous post, I set out my arguments for the importance of research-evidence for teachers.

If you are interested in our project, or can provide us with extra guidance, please contact me through Twitter @atharby.