This is my eighth year as a secondary English teacher. I teach a full timetable of lessons and it would be a fair estimate to say that I spend, on average, an hour a day marking… or in other words over 8 full days an academic year bent over a never-ending pile of biro-scrawled offerings.

At the beginning of this year, I decided to take a step back. What is time well spent and what, quite frankly, is a waste of time? Could I realistically cut down the marking hours, yet continue to have a positive impact on my students? Or even better: could I claw back precious time, yet have an even greater impact on student progress than I once did. Minimum effort for maximum pleasure, you might say.

With this in mind, I have devised a strategy of using symbols, rather than laboriously writing out repeated comments in the students’ books. Have a look at this slide:

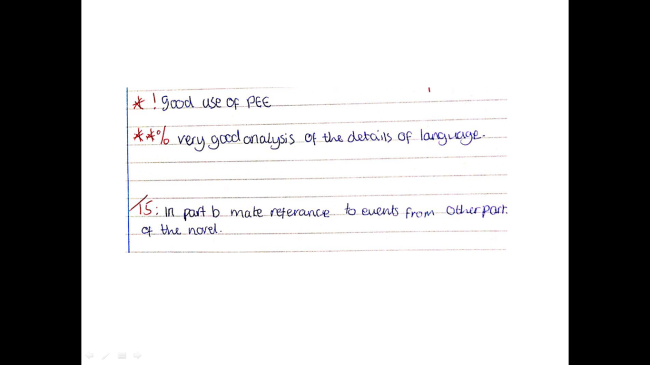

I had been marking a class set of Y10 essays on John Steinbeck’s Depression-era novella Of Mice and Men. Instead of writing out comments slowly – and slowly it must be; my handwriting is pitifully awful – over and over again, I scribbled praise comments and targets on a piece of paper. In their books I used symbols in their place. If, for instance, a student had shown analysis of language at B-standard, I would write **%; if they also needed to improve the way they made links to the novel’s context, I would write T4. Each time another student required similar praise comments or targets, the symbol could be repeated. Stars for ‘good’, ‘very good’ and ‘excellent’; symbols for the criterion successfully hit. As new praise comments and targets became necessary, new symbols were produced and quickly added to the handwritten list. When the work was handed back, students copied them from the PowerPoint slide I had quickly produced. Simple.

What I love about this system is that praise and targets are not pre-ordained (as it would be with a generic target list worked out before I had started marking). The targets are instead my direct response to their work – and thus still individualised. It also means that:

- Students have to read their comments as well as their grade. (There is a lot of research to suggest that students rarely read comments when coupled with a grade.)

- Lesson time is not wasted deciphering my handwriting – Sir, does this say ‘elephant’?

- Praise is much more focused on assessment criteria than it once was.

- I win back in the region of one minute per student, or, let’s say, an hour a week.

- It can be used again – modifications necessary of course – next time round. It is also a useful tool for guiding future peer- and self-assessment.

So where next? There has been a lot of buzz on twitter lately about DIRT (Directed Improvement and Reflection Time). Too often in the past, I have assiduously set targets, yet left it at that. Right, kids, there’s your Of Mice and Men target – now we’re doing Shakespeare. Without time to act upon them, targets are left to rot… and rot they do.

The target symbols can really help with DIRT, as they can be linked to scaffolded tasks that support improvement:

This, however, is not without its pitfalls. As I have discovered, the DIRT tasks do not always miraculously lead to oceans of beautifully sustained progress. The student below was set T7 (see slide above):

The left hand piece was his original paragraph; the right hand his improved one. He has hit his target – improving his expression through better vocabulary choices – yet only superficially so. The link between the quotation and the 1930s context is woolly to say the least in the second as well as the first paragraph. There is still not sufficient explanation as to why the phrase ‘one behind the other’ demonstrates that they were ‘very close friends’ or ‘had a strong companionship’. Something else was needed.

Yet, in other circumstances it worked well. This student was asked to write a completely new paragraph (on the right hand side) in response to part b of the question.

Her second attempt is a significant improvement on her first, if, albeit, a paragraph with a very different focus. On reflection, it seems to me that the first student was in fact completing a reflective task, rather than an improvement task. By asking him to rewrite a failed paragraph, he was always going to be restricted by the limitations of his first attempt – trapped forever, you might say, in its clunky assumptions. The second student had more of a chance to improve because, quite simply, she had been given a task that genuinely gave her the freedom to do so.

My DIRT strategy from now on will be two tiered:

- Students begin by reflecting on their original piece by correcting SPG errors, improving vocabulary and responding to any questions I have written in their books (writing these could also be streamlined with a symbols approach).

- They will then complete a written task, free from the shackles of their original offering, with the aim of improving their work by focusing on one target I have set and one target they have chosen from the list.

And this is precisely what time-saving strategies are about. They release us from our – too often – self-imposed prison cells to allow us the thinking space to become truly reflective. Minimum effort really can lead to maximum pleasure; our students can only benefit as a result.

Pingback: Verbal Feedback Given…. | Class Teaching

Pingback: The beauty of paired writing | Reflecting English

Pingback: Challenges Ahead | Class Teaching

Pingback: Feedback matters | Class Teaching

Pingback: Fast Feedback | Belmont Teach

Pingback: Strategic marking for the DIRTy-minded teacher | Reflecting English

Pingback: Time-management in education: a win-win solution? | Reflecting English

Pingback: What if we didn’t mark any books? | Reflecting English

Pingback: Feedback on feedback! | Meols Cop High School

Pingback: Feedback: built-in or added-on? | Reflecting English

Pingback: 4 Steps to Efficient Effective Marking by @Powley_R | UKEdChat - Supporting the Education Community