Image: @jasonramasami

Image: @jasonramasami

At #tlt14 last weekend I had the pleasure of chatting with blogger and all-round nice chap Phil Stock about the role of knowledge in English teaching. Phil argues that student-generated interpretations of literary texts almost always lack depth and sophistication. Instead, textual interpretations are often better taught as discreet knowledge, rather than relying solely on the flimsy attempts of our students. In other words, we owe it to them to teach interpretations of texts as explicit knowledge rather than hoping that we can teach them the skill of interpretation. Because an interpretation is formed in the context of what is already known, only children whose upbringings have been steeped in a wealth of cultural references have any chance of generating a genuinely sophisticated one.

Teaching for knowledge is not a simple concept in English. This is because we have to work out which and whose knowledge to teach. For traditionalists, this is where the Matthew Arnold argument comes into play: the ‘best that has been thought or said’ school of thought. But even if we took the Arnold line as gospel, the substance of taught knowledge would remain very different depending on which school, or even classroom, the child attends. In fact, two students steeped in traditional knowledge-based teaching might finish a GCSE course with completely different textual knowledge – Hamlet and Great Expectations rather than Othello and Jane Eyre, for instance. If we eschew the canon and teach a more eclectic range of texts, the problem becomes more extreme. I wonder if this confusion is partly the reason why the skills-based model of English teaching has become such a seductive alternative.

Indeed, for many years I have taken it as axiomatic that English is a skills-only subject. As such, texts and topics are useful only as reference points for developing nebulous skills – be it ‘making inferences’ or ‘charting the development of a character’ – with limited value in and of themselves. I am now realising that the problem is not that the skills should be considered unimportant, but that the resultant teaching approaches can inhibit learning.

Skills-based teaching lacks specificity. It encourages us to share abstractions, often in the form of learning objectives, success criteria or written and verbal feedback targets. A statement that I have used on many an occasion is ‘you need to use a broad range of vocabulary‘. It might seem straightforward to put into action, but it is not. Students can be left confused by which words to use and where to use them.

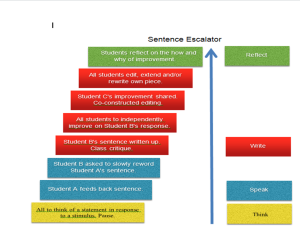

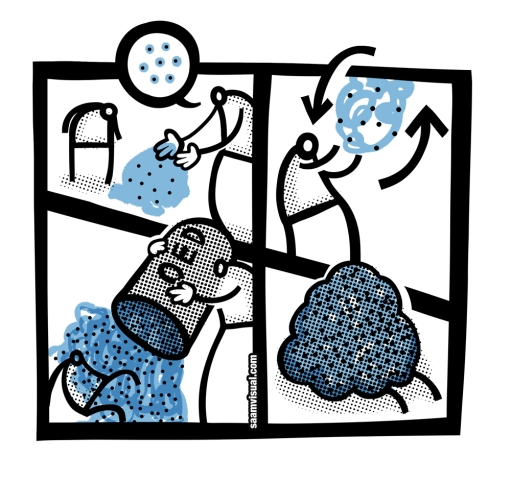

If we adopt a knowledge-based approach to teaching vocabulary, things become simpler and a hell of a lot clearer. We can decide on a set of words we would like them to use, ensure that they practise them accurately in a range of contexts, and then reasonably expect the new vocabulary to be put to use in extended writing and remembered in the long-term. Just ten interesting words explicitly taught over a half term – or three-hundred words over the five years of secondary school – is eminently more manageable and more sensible than dropping students into the bottomless deep blue of The Oxford English Dictionary so that they can flounder time and time again. (This idea is brilliantly illustrated in Jason Ramasami‘s image at the top of this page.) Many other words will naturally be picked up in that time too, let’s not forget. However, the irony is that by focussing on the mastery of small, discreet items knowledge in the short term, we could accumulatively achieve so much more in the long term.

This approach, however, might rub against some deeply-held beliefs about what English teaching should constitute. We want our students to be free and individual, to produce work of flair and originality, so why deny this by encouraging uniformity? When we direct students towards specific vocabulary it is inevitable that there will be less diversity in the final written product produced within the class. This can leave us feeling cheap, like we have cheated our students out of the chance to be creative. But does it matter?

It is highly unlikely that a maths teacher would feel similarly. If every student achieves one-hundred percent in a maths test, and every student uses exactly the same working-out method, I imagine a teacher will feel that they have done a pretty good job. Now in English, work will never be identical, nor should it be. But does it really matter if the final product is similar because students are all practising the same concrete knowledge? In our quest for student divergence have we neglected to consider that all our students – even our brightest – need a secure base to start from?

Vocabulary is just one example where a focus on concrete knowledge, taught with the expectation that students will remember it and use it correctly in context, might reap benefits. Another example comes in the teaching of literature. To achieve between a B and an A* for the AQA English literature controlled assessment – which makes up 25% of the final grade – a student must develop ‘interpretations’. But as Phil explained, how well can novice readers, who in many cases have had little prior exposure to literary texts, make valid interpretations?

Inferences about a text are based on knowledge. We read that a character sits on a wall with their head in their hands and we infer that she is unhappy and dejected. The inference comes mainly from our knowledge of the world – that when someone puts their head in their hands it usually indicates a negative emotion. I would argue that most inferences made by students at KS3 and KS4 are drawn from their general knowledge of the world, not their knowledge of literary devices, conventions or other literary texts. Take the opening of Of Mice and Men. Almost all students will miss the biblical allusion in the description of the clearing ‘down by the river’ (used by Steinbeck to amplify the simple purity of George and Lennie’s companionship) because they do not securely know the Garden of Eden story and they do not realise that such allusions are a literary convention.

To teach ‘interpretation’ I have often expected students to do the work for themselves. Pedagogically, this has taken the form of in-depth questioning with the hope that I can elicit something that is hiding away in the deepest recesses of their minds. This has often, but not always, proven unsuccessful and I have had to backtrack and override the unfocussed ideas I have elicited. There is a critical question that cuts to the core of English teaching. At what point do we stop telling a student the answer and start asking questions? I think that, for many years, I have been asking the questions before securing the knowledge needed to answer them.

The solution might be to teach interpretations of a text as discreet knowledge. In this case, to talk through the Garden of Eden story – some will know it well, others will not – and how and why Steinbeck has alluded to it. So that they are involved in cognitive work, students can search for the textual details that support the theory. Teaching interpretations as concrete knowledge will be anathema to some teachers, but it is through this approach that we model how to make an interpretation. When students have grasped new ideas and can write about them with some fluency, they have achieved something valid. To accuse them of ‘idea plagiarism’ because they have taken ownership of an idea we have given them, or to misappropriate teaching as ‘spoon-feeding’, is very unfair. It is worth considering, too, that most teachers will actively research a range of interpretations to share with their students before teaching a new text. If teachers are intuitively aware that forming an interpretation is no easy feat, why do we expect it from our novice charges? I think interpretation is better thought of as an end rather than a means.

So, my key point is that in our desire to engender creativity in our students, might we be denying them the chance to learn English in a concrete knowledge-based way, in a way that will eventually guide them towards the independence we so desire from them? Since I have taken a more convergent approach and tightened my parameters, two things have occurred. One, student work has become more similar. Two, student work has become better.

Please do not take this as an argument against imagination. I think it is fair to say that some students are better at using what they already know to make interesting inferences and interpretations and to devise compelling written pieces than others, and that this should be actively encouraged. Knowledge teaching can sit side-by-side a celebration of the imagination; the two do not have to work solely in opposition. However, it is our responsibility to teach children new things, not to simply rely on what they already know. By teaching new knowledge in a simple and explicit way, we reduce cognitive load and probably increase the potential for creativity in the long-term.

Often this will mean changing the ratio between what we tell them to do and think and what we expect them to do and think individually.

Related posts:

The unheralded beauty of repetition